Kate Bolick Shares Her 'Spinster Wishes' With Single Women Everywhere

By : Huffington Post | Category : Divorce News | Comments Off on Kate Bolick Shares Her 'Spinster Wishes' With Single Women Everywhere

22nd Apr 2015

Kate Bolick is a self-proclaimed “spinster.” She’s over the age of 40, unmarried and — gasp! — happy.

In 2011, when she was 39, Bolick wrote a cover story from The Atlantic titled “All The Single Ladies.” And it was her face on the cover of the magazine instead of that of stock photo model, with the tagline “What Me, Marry?” emblazoned across her body in bold block letters. The story — which posed the question one would hopefully always say yes to, “Can I spend my life alone and still be happy?” — gave way to a thousand thinkpieces, and eventually, a book deal for Bolick.

The result is Spinster: half memoir, half historical views of singledom. Bolick situates her own life within the context of today’s reality — both marriage rates and birth rates have reached historic lows — and within the lives of five women whose work influenced her greatly, women whom she refers to as her five “female awakeners.” Those awakeners are Edith Wharton, Neith Boyce, Maeve Brennan, Edna St. Vincent Millay and Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

That Spinster is first and foremost Bolick’s story will make the narrative deeply familiar to some single women, and likely unrecognizable to others. But that comparison and inner dialogue is what Bolick wants from her readers. “I wanted to show the conversation that I’d been having in my head with these women from the early 1900s, and I thought that by putting my own life on the page along with theirs, then the reader could replicate the experience that I’d been having with the women I’d been reading about,” she said to The Huffington Post over the phone last week. “I want whoever is reading the book to be in conversation with me — agreeing with me, disagreeing with me.”

Bolick may have written a book all about what it means to be unmarried, but her ultimate point is that “single ladies” are so much more than their relationship status. “It’s almost as if the single person is still not a real, live person, with her own range of experiences,” she said. “We have not seen the single experience represented in all its complexity ever, really. So because of that, we’re stuck thinking of the single woman as a static being.”

The Huffington Post spoke with Bolick about her new book, her “spinster wishes” and what it all means for today’s 20 and 30-something single women.

In the opening of the book, you say that “whom to marry and when will it happen” are two questions that dominate every woman’s existence. How do these questions shape the way women see their lives?

I’m glad you’re focusing on the word “questions,” ‘cause that’s the point of that statement. I see these questions as defining the female experience because culture expects us to get married, and so we grow up assuming we’ll get married some day. That question is always there — when will I and who will it be? And possibly you get to a point where you decide you don’t want to get married, but it’s something you have to reject.

What has it meant for men that they haven’t historically been forced to define their lives by these questions?

It means for one, that how to answer them is far less freighted for men. Men too assume that they will one day marry, it’s not just a female assumption, but because traditionally men have been less defined by it than women have, it’s something that they’re able to have a more casual relationship to the idea of, or just trust that it’ll happen someday. Historically, we’ve put the power in the man’s hand, because the man is the one who proposes or he’s the chooser of the mate. So men grow up thinking that sure, this is something that they’ll do someday, whenever they feel like getting around to it. With women, it’s a more passive experience. They assume it’s something that they’ll do, but they don’t know when or how.

You talk about why you love the word “spinster.” At what point did you land on Spinster as your book’s title?

I was in Toronto visiting my friend Michael, who I write about in the book, who is a professor at the University of Toronto. He wrote an academic book a couple of years ago called Single: Arguments for the Uncoupled, and talking about this is something we do all the time. He came up with the title. Not only have I always liked the word and the idea of the spinster, but I like how it broadcasts an historic angle. It’s a book that’s about history as well as the contemporary experience. “Spinster” is also a word that people have very strong reactions to. I had to spend a lot of time convincing my publisher that this was a good idea, because they thought it was going to scare off readers, that no single woman wants to sit on the subway reading a book called Spinster. But I think it’s been something that’s been bubbling up over the past few years — women my age talking or thinking about “spinsterdom.” So I think there is some warmth around the word as well.

You also mention our inability to really remember how things looked beyond the experience of our parents and grandparents. When you dug into the history of single women in the U.S., what did you learn that surprised you most?

The biggest surprise was that the single woman hasn’t always been derided. There were moments in history where single women were embracing their single status and talking about it with each other, and even perceived positively by the culture. [Feminist, sociologist and author] Charlotte Perkins Gilman, for example, was born in 1860 and she came of age in what I think of as the Golden Age of the Aunt or Great-Aunt, where the women who were her aunts, the women of the 1830s and ‘40s were actively and publicly choosing not to marry. It wasn’t a mass movement, but that thinking and energy were in the air, so by the time Gilman was growing up, she had examples of very strong, singular, unmarried women in her family tree. She could see that marriage was a choice and not a necessity. We tend to think that people have always been coupled, always been married, and completely forget that there is this long history of people who have lived outside of those arrangements and thrived there.

You write about your “spinster wishes.” What is it that you always found so appealing about the fantasy of solitude and independence, even when you’ve been in relationships that on paper seemed perfect?

I read through all of my journals and was shocked to see myself writing about the “spinster wish.” That was remarkable to me, that even at 21 and 22 I was glamorizing and romanticizing the idea of the woman alone. I think that was because I’m such a relationship-oriented person.

Back in my 20s, when I was in relationships all the time, solitude was something I was always stealing. It always felt like a stolen good I had to treasure but that I couldn’t count on having. Those moments felt charged and very exciting. I have a very different relationship to alone-ness and solitude now, because now it’s what I do all the time. So it’s not this charged, exciting thing — it’s just the way I live my life. But that’s the way I wanted it. I didn’t want to want to be stealing time for myself. I wanted time for myself to be the fundamental way that I live.

Do you feel like you had a moment where you had a realization that being alone was something you could choose?

It was definitely in my late 20s, when I was thinking very seriously about the relationship that I was in, and where we would go, and realizing that — wait a minute — I had never been alone in my life. How could I expect to be someone’s life partner if I don’t know how to take care of myself yet? So that really felt like a revelation. I was driven by an impulse that I didn’t really understand, which felt very frightening. And then once I was alone and living on my own, I thought, “This will just be a temporary thing. I’ll just do this for a couple of years. And during that time I’ll learn about myself and how to take care of myself and then I’ll be ready to partner up with somebody.” I was very surprised that I kept never wanting to do that. I was still entering into relationships assuming that it would go forth down a particular trajectory, and then culminate in: to marry or to not marry. I didn’t know how to undo that way of thinking about things.

In my early 30s, I was still assuming that I’d meet someone and be struck by lightning and want to marry him, and I kept being surprised that that didn’t happen. And along the way, I grew into this way of being.

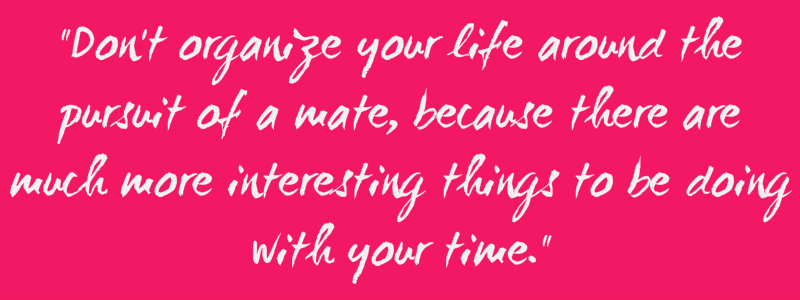

Is there something you hope single women in their 20s take away from reading about your experiences?

That these years alone can be an incredibly rich period of your life and it’s not something to be feared. Don’t organize your life around the pursuit of a mate, because there are much more interesting things to be doing with your time. And have love and romance be part of it — I think it’s essential to most people’s lives — but there doesn’t need to be so much anxiety around whether or not you’ll find a person. That will happen in its own time.

At the end of book, you say that this dichotomy between single vs. married is a false one. Why do you think we have a tendency to see just two camps of women — single and married — when our lived experiences aren’t limited in that way?

Isn’t it astonishing that we can’t stop seeing it in this very reductive way? I think part of it is that we still don’t fully understand the single female experience, because we haven’t seen it reflected and represented enough. We understand the married person and the married experience, and then the single person is still inscrutable. It’s just easier to create this false dichotomy.

Another image that looms large in the minds of single women is of the “crazy bag lady” or “crazy cat lady.” Why do you think it is that this fear of being alone is a) so terrifying and b) so tied up in finding a (presumably male, heterosexual) romantic partner?

I think it has a lot to do with the fact that women still find a lot of social and personal validation in the idea of being chosen by a man. Obviously not all women feel that way, but I think that [idea] is pretty pervasive. And because the ultimate social validation is being loved by a man — whether or not you’re married to him — not being loved by a man is the worst possible thing. So that’s why the specter of the crazy bag lady who lives on the streets is so threatening. She’s the ultimate example of what it means to not be loved.

It’s just crazy to me the power that image still holds, even amongst powerful, successful single women. There’s this incredible disconnect between what we know to be true intellectually and the emotional part, which is harder to conquer.

Exactly. And I want the book to be speaking to the emotional aspect of it — to show my own insecurities and fears throughout this process. It’s something we struggle with, and that’s OK, to some extent. It’s important stuff, how we spend our life and who we spend our time with. And it requires a lot of thought. But I would hope that a young woman could read my book and see the amount of insecurity I went through and maybe she could learn to not be as insecure. Because I shouldn’t have been as afraid as I was at certain points.

What can we do to free ourselves from that fear dominating our lives?

For me, when it happened was when I didn’t marry by 35 or 36. I had another one of these “aha!” revelatory moments. I thought, “Oh, I didn’t do it when I was supposed to. I didn’t get married on the expected timeline. So this means it might never happen — or that it might happen at any time. It could happen in 10 years or 20 years or next year.” And that freed me. I wasn’t chasing after marriage as a brass ring. And yet, still, it was something I thought I was supposed to be doing.

I think another piece of this is de-emphasizing the primacy of romantic love in the couple, and making yourself alive to all of the relationships in your life that are positive and sustaining. So rather than being a singular alone person looking for a mate, recognizing that you live inside of a constellation of relationships that sustain you and are valuable to you.

Do you feel as though single women are having a particularly visible moment right now?

Oh absolutely. I think it’s really exciting. It’s so different than 15 years ago when I was first starting to think about these things in earnest. There was no productive or interesting conversation around the single woman. And now we’re really thinking about it.

— This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

Online Case Evaluation

Blog Topics

- Divorce matters (3)

- Divorce News (720)

- Miscellaneous family law matters (1)

- Modification matters (1)

- Video (2)